The final pictures from NASA’s 13-year-long Cassini mission at Saturn are flowing in – and they’re good to the last drop.

Or even better, good to the last moonset.

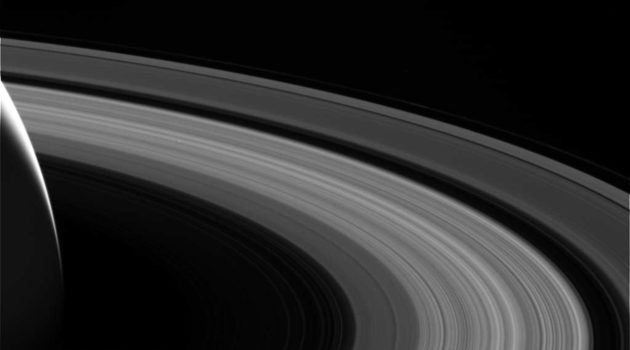

Raw images, captured by Cassini’s cameras during the run-up to the bus-sized spacecraft’s scheduled destruction on Friday morning, have been popping up by the dozens on NASA’s mission website.

Among the still-image sequences are pictures showing Enceladus, an ice-covered moon that could conceivably harbor life, as it sets on the Saturnian horizon.

The Planetary Society’s Emily Lakdawalla assembled the photos into a nifty little animation:

Here is Enceladus setting, with all the animation frames aligned on Enceladus. pic.twitter.com/1JfJ0FWino

— Emily Lakdawalla (@elakdawalla) September 15, 2017

The pictures come down looking like black-and-white photographs, but they’re actually multiple views taken through different filters. NASA will eventually come up with the “official” color combination, but in the meantime, Lakdawalla and others who are adept at image processing are putting out their own versions – sometimes after multiple tries:

https://twitter.com/elakdawalla/status/908478101197283329

https://twitter.com/koujiohnishi/status/908492736415776773

https://twitter.com/JPMajor/status/908543296087007232

https://twitter.com/JPMajor/status/908481870404493312

https://twitter.com/_RomanTkachenko/status/908604786945208320

https://twitter.com/Astropartigirl/status/908513460027252736

There’ll be much, much more to come in the hours ahead, but pictures won’t be the last things that Cassini sends back: Toward the end, the spacecraft will switch to sending data about the composition of Saturn’s upper atmosphere, magnetosphere and radio environment, at a transmission rate that’s low enough to make sure the data’s received by radio antennas back on Earth.

The end will come at 4:55 a.m. PT Friday, when Cassini dips so low into the atmosphere, at such a blazingly fast speed of 76,000 mph, that the spacecraft breaks up and vaporizes.

It’s all part of NASA’s plan to dispose of the orbiter in such a way that there’s no risk of contaminating Enceladus or Saturn’s smog-covered moon Titan, another potential home for alien life. Those moons are likely to be the focus of future space missions, and scientists want to make sure their natural state is preserved for when that day comes.

A similar scenario played out in 2003, when NASA’s Galileo orbiter dove to its destruction in Jupiter’s atmosphere. That was done to make sure that spacecraft didn’t smash into Europa, an ice-covered Jovian moon that’s thought to harbor a hidden ocean.

Now NASA’s Europa Clipper is due to head out in the 2020s to take a fresh look at that moon – and if the stars align, someday a future space probe will catch a closeup of Enceladus and Titan rising again.

NASA TV will stream live commentary on the end of the Cassini mission from 4 to 5:30 a.m. PT Friday, followed by a post-mission news conference at 6:30 a.m. PT. Check out YouTube for a 360-degree view of JPL’s Mission Control as the witching hour arrives.